- News

- Science & Astronomy

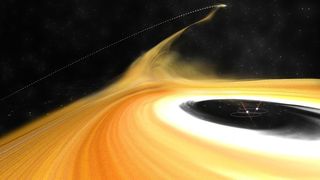

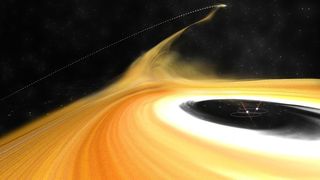

An artist’s depiction of an intruder star disrupting an infant planetary system.

Image credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO), B. Saxton (NRAO/AUI/NSF)

About a billion years from now, the sun will have become much bigger, brighter, and hotter, likely leaving Earth uninhabitable. However, a chance encounter with a passing star could save our planet by tossing it into a cooler orbit or helping it break free of the solar system entirely, a new theoretical study suggests. (Still, the chances of that happening are extremely slim.)

Today, Earth lies within the sun’s habitable zone, a ring-shaped region within which planets may harbor liquid water. But our planet’s situation will worsen as the sun grows over the next billion years, pushing this zone outward and away from Earth. That means liquid water — and, therefore, life — could become history well before the sun balloons into a red giant and swallows Earth entirely 5 billion years from now.

But what if Earth were ejected from its orbit to become a free-floating, “rogue” planet? To investigate this possibility, a team of astronomers simulated how our solar system would behave if a star swept past it at some point in the next billion years — an event they knew could kick planets out of orbit. Their study has been accepted for publication in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society and is available in the preprint database arXiv.

Related: New clues emerge about runaway star Zeta Ophiuchi’s violent past

Stellar flybys of this kind have happened in the past.

“Currently, the closest approach of any star is about 10,000 au [astronomical units] (and happened a couple of million years ago),” lead study author Sean Raymond, an astronomer at the University of Bordeaux in France, told Live Science by email. That’s 10,000 times the distance from Earth to the sun. But just to see what would happen, the team calculated planetary movements when stars of different sizes approached at various distances, even as close as 1 au.

The researchers produced 12,000 simulations. In some of them, the star’s passage pushed Earth into a farther, colder orbit. In others, our planet (along with some or all of the other planets) landed in the Oort cloud, the spherical shell of icy objects believed to sit at the outermost edge of the solar system.

More intriguingly, in a handful of simulations, the wandering star managed to gravitationally lure Earth away with it, capturing our planet in its free-wheeling orbit through the cosmos. According to Raymond, Earth, in this case, “could in principle end up on an orbit receiving enough energy for liquid water” from our new home star.

Still, it’s best not to put your money on a stellar savior. All these possibilities together amount to just a 1-in-35,000 chance that life on Earth will survive after the star whirs by,